Refugees’ plight is worsening as their numbers grow and their nature changes

THEY are fast approaching 1m and their future is bleak. It is unlikely that the refugees who have fled the ghastly war in Syria will be able to return home anytime soon. Nor are many likely to start a new life abroad. They live in camps or shared rooms in neighbouring countries. They cannot work. Health care, education and other services are vestigial. “We are alive but not living,” says Yasser Jani, a 39-year-old chemistry teacher who, with his wife and children, has been in a camp in southern Turkey since July 2011.

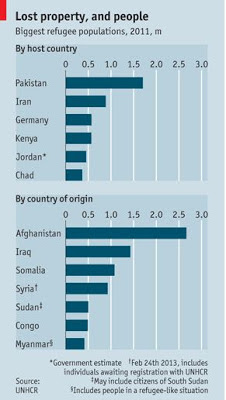

The plight of Syria’s refugees exemplifies a growing global problem. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) counts 15.2m (4.8m of them Palestinians, looked after by a different UN outfit), with an additional 26.4m displaced within their own lands. But hosts are increasingly unfriendly to refugees, and ever more unwilling to allow them to settle permanently. Conflicts are becoming more protracted. The old ways of dealing with people fleeing across borders, designed for smaller numbers and shorter stays, rarely work anymore. The difference between refugees and economic migrants can be blurry; so is the standard of living of the new arrivals and the worst-off in the countries they arrive in.

Reluctance to accept refugees is growing. Even countries that have signed the UN’s Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, approved in 1951, are often loth to recognise asylum claims. Others are harsher still: unwilling in some cases to consider any uninvited guest as a refugee.

TunTun, a 41-year-old Karen from Myanmar, has spent 20 years in Thailand’s Mae La camp. He dare not return home, but cannot go elsewhere. The Thai authorities have not signed the convention and class people like him as illegal migrants. Some states try to turf them out. In 2007, for instance, Malawi’s government closed one of two camps for people from war-torn states including Rwanda and Somalia. President Joyce Banda has mooted closing the second, arguing that its population has been there too long.

At best, refugees have recognised status and are allowed to stay but even then most remain dependent on agency handouts or informal work to survive. Many are barred from public services such as health care or education. The number of those living in such limbo is increasing, mostly because more stay away from home for longer, or permanently: three-quarters of those registered with UNHCR have been in exile for five years or more.

Another reason is that the economic crisis has made rich countries stingier. America and Canada took in almost all of the 200,000 Hungarians who fled the 1956 uprising. Today more countries have resettlement programmes, but the numbers they take are only a tiny slice of the world’s refugee population. In 2011 only 62,000 were accepted; in 2012, it was 68,589.

Only rarely does a country raise its intake, as Australia did after many cases of people dying while trying to row there. The rich world is also cutting back on what it spends on aid to refugees. “The burnout is astonishing,” says Dawn Chatty who heads the Refugee Studies Centre at Oxford University.

Refugee populations are also more mobile than they used to be. Fund-raising pictures may still depict shoeless Africans in camps. But many refugees today are middle-class people crammed into cheap flats. That is the fate of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis who fled sectarian bloodshed in 2006 for neighbouring Damascus and Amman. Their needs were not food, water and shelter, but psychological care and education. Some family members tried to commute to homes and businesses in Iraq.

Nought for your comfort

Aid agencies have had to adapt. UNHCR sends text messages with information; the World Food Programme mails electronic grocery vouchers, which give recipients more choice and remove the need for costly distribution networks. UNHCR, which once liked refugees to stay in easy-to-reach camps, now says it prefers them to lead a normal life in urban areas.

More refugees mingle with local people and more than 80% flee to poor countries already struggling to provide for their own citizens. Helping them increasingly resembles development aid, explains António Guterres, the head of UNHCR. Rather than providing services just for people registered with it, the agency works ever more closely with the governments and populations in countries that people flee to.

Before the war started in Syria, the UNHCR gave money to the country’s government to employ more teachers and doctors in schools and hospitals frequented by Iraqis. To prevent people getting envious, some charities set up services for all locals. The 2,800 people who took part in activities in Damascus for traumatised children set up by International Medical Corps, a California-based charity, were a mixture of Iraqis and Syrians.

David Apollo Kazungu, Uganda’s Commissioner for Refugees, says it no longer makes sense to treat refugees as a humanitarian issue. “Those who stay for years throw up developmental problems for us, such as how to find enough land, water and jobs for everyone,” he argues. Uganda has already tried to improve the lot for the nearly 200,000 refugees it hosts by placing them in settlements rather than camps, and by giving them land to farm.

Mr Kazungu believes that naturalising long-term refugees in the mainly poor countries they flee to would allow them to work and give them access to all public services. In return, he says, rich countries should give development cash and advice to host countries. His government wants to make it easier for refugees to apply for Ugandan citizenship, something Tanzania has already allowed. Regional agreements could help neighbouring countries share the burden of accepting extra people.

Better treatment for refugees may be no easier to sell in poor countries than rich ones. But officials reckon that accepting refugees could turn a burden into a benefit. Allowing them to work would increase economic activity and as citizens they would have to pay taxes. In some countries UNHCR is trying to move things in this direction. With funding from IKEA it has set up centres in Sudan and Bangladesh that offer training rather than handouts. The agency also asks host countries to let refugees work legally.

Though many refugees long for a more normal life, permanent solutions will not always work. Victims of the world’s most protracted modern refugee crisis, the Palestinians, for instance, do not want a new nationality because it would erase their right of return. More than six decades on, grandchildren proudly display the keys to their families’ former houses.

The plight of Syria’s refugees exemplifies a growing global problem. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) counts 15.2m (4.8m of them Palestinians, looked after by a different UN outfit), with an additional 26.4m displaced within their own lands. But hosts are increasingly unfriendly to refugees, and ever more unwilling to allow them to settle permanently. Conflicts are becoming more protracted. The old ways of dealing with people fleeing across borders, designed for smaller numbers and shorter stays, rarely work anymore. The difference between refugees and economic migrants can be blurry; so is the standard of living of the new arrivals and the worst-off in the countries they arrive in.

Reluctance to accept refugees is growing. Even countries that have signed the UN’s Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, approved in 1951, are often loth to recognise asylum claims. Others are harsher still: unwilling in some cases to consider any uninvited guest as a refugee.

TunTun, a 41-year-old Karen from Myanmar, has spent 20 years in Thailand’s Mae La camp. He dare not return home, but cannot go elsewhere. The Thai authorities have not signed the convention and class people like him as illegal migrants. Some states try to turf them out. In 2007, for instance, Malawi’s government closed one of two camps for people from war-torn states including Rwanda and Somalia. President Joyce Banda has mooted closing the second, arguing that its population has been there too long.

At best, refugees have recognised status and are allowed to stay but even then most remain dependent on agency handouts or informal work to survive. Many are barred from public services such as health care or education. The number of those living in such limbo is increasing, mostly because more stay away from home for longer, or permanently: three-quarters of those registered with UNHCR have been in exile for five years or more.

Another reason is that the economic crisis has made rich countries stingier. America and Canada took in almost all of the 200,000 Hungarians who fled the 1956 uprising. Today more countries have resettlement programmes, but the numbers they take are only a tiny slice of the world’s refugee population. In 2011 only 62,000 were accepted; in 2012, it was 68,589.

Only rarely does a country raise its intake, as Australia did after many cases of people dying while trying to row there. The rich world is also cutting back on what it spends on aid to refugees. “The burnout is astonishing,” says Dawn Chatty who heads the Refugee Studies Centre at Oxford University.

Refugee populations are also more mobile than they used to be. Fund-raising pictures may still depict shoeless Africans in camps. But many refugees today are middle-class people crammed into cheap flats. That is the fate of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis who fled sectarian bloodshed in 2006 for neighbouring Damascus and Amman. Their needs were not food, water and shelter, but psychological care and education. Some family members tried to commute to homes and businesses in Iraq.

Nought for your comfort

Aid agencies have had to adapt. UNHCR sends text messages with information; the World Food Programme mails electronic grocery vouchers, which give recipients more choice and remove the need for costly distribution networks. UNHCR, which once liked refugees to stay in easy-to-reach camps, now says it prefers them to lead a normal life in urban areas.

More refugees mingle with local people and more than 80% flee to poor countries already struggling to provide for their own citizens. Helping them increasingly resembles development aid, explains António Guterres, the head of UNHCR. Rather than providing services just for people registered with it, the agency works ever more closely with the governments and populations in countries that people flee to.

Before the war started in Syria, the UNHCR gave money to the country’s government to employ more teachers and doctors in schools and hospitals frequented by Iraqis. To prevent people getting envious, some charities set up services for all locals. The 2,800 people who took part in activities in Damascus for traumatised children set up by International Medical Corps, a California-based charity, were a mixture of Iraqis and Syrians.

David Apollo Kazungu, Uganda’s Commissioner for Refugees, says it no longer makes sense to treat refugees as a humanitarian issue. “Those who stay for years throw up developmental problems for us, such as how to find enough land, water and jobs for everyone,” he argues. Uganda has already tried to improve the lot for the nearly 200,000 refugees it hosts by placing them in settlements rather than camps, and by giving them land to farm.

Mr Kazungu believes that naturalising long-term refugees in the mainly poor countries they flee to would allow them to work and give them access to all public services. In return, he says, rich countries should give development cash and advice to host countries. His government wants to make it easier for refugees to apply for Ugandan citizenship, something Tanzania has already allowed. Regional agreements could help neighbouring countries share the burden of accepting extra people.

Better treatment for refugees may be no easier to sell in poor countries than rich ones. But officials reckon that accepting refugees could turn a burden into a benefit. Allowing them to work would increase economic activity and as citizens they would have to pay taxes. In some countries UNHCR is trying to move things in this direction. With funding from IKEA it has set up centres in Sudan and Bangladesh that offer training rather than handouts. The agency also asks host countries to let refugees work legally.

Though many refugees long for a more normal life, permanent solutions will not always work. Victims of the world’s most protracted modern refugee crisis, the Palestinians, for instance, do not want a new nationality because it would erase their right of return. More than six decades on, grandchildren proudly display the keys to their families’ former houses.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento

Nota. Solo i membri di questo blog possono postare un commento.